The Games Children Play

Oh, the games people play now. Every night and every day now.

Never meaning what they say now. Never saying what they mean.

— Joe South – Games People Play (1969)

We didn’t have cable TV, we weren’t able to stream videos, and we didn’t have an endless supply of music or the ability to interact with strangers around the world, but we were seldom bored. (And if you were, the last thing you’d want to do was tell your mom about it, because she’d find something to occupy your time right quick.) This was due to us having a collective storehouse of games.

No one taught us these games or told us to play them. They just were. And it is worth remarking that we lived in a rural area with little outside contact, yet the games came to us, spontaneously and intact, passed down through the ages, like Race Memory. I can’t say this for certain, but I believe mine was the final generation where this happened. I don’t recall my children playing many of these games, and I can’t imagine any children today embracing such low-tech pastimes.

One of the earliest I recall was Fox and Geese. I was so young when we played this that I forgot the rules and had to look them up. I found them, much to my chagrin, on a website entitled “Colonial Games,” and I quote:

How do you play fox and geese in colonial times?

(Not to be confused with the board game of the same name.)

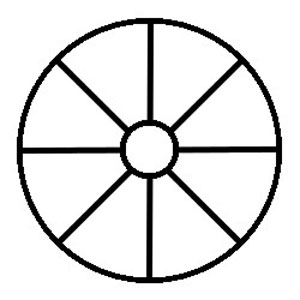

Fox and Geese was a tag game Colonial children liked to play during winter because they could make the wheel shape they needed easily in the snow.

The circle in the middle of the wheel is the base for the geese. Starting at the base, the Geese have to run on the lines of the spokes and rim of the wheel while the Fox chases them. If the Fox tags any of the Geese, they also become Foxes and chase down the remaining Geese to tag them.

I’m surprised, and just a little insulted, at being referred to as “Colonial.” It was 1960, not 1760; we had indoor plumbing and everything. However, I suppose, to children today, it might as well have been the Victorian Era, and the customs would appear just as strange.

The concept of It, for all I know, may be lost to time by now, and I am certain some of the methods for choosing who would be It have, rightly, faded away. The person who was It was, well, It. In Fox and Geese, they would be the Fox, in Tag, they would be the one to chase the others, in Duck, Duck, Goose, they were the one… But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Like the other Colonial children, we played Fox and Geese in the winter, and for the same reason: we could make the maze in the snow. There were not a lot of us around, but on a good day, we could scare up about six or seven players, and that was enough.

For this, and any other game, we selected who would be It by the time-honoured methods of “One potato, Two potato, Three potato, Four…” or “Eenie Meenie Miney Mo…” In both these methods, all participants would stand in a circle and put their fists out.

the toe, if he hollers let him go…

The person doing the rhyme (no idea how that person was picked) would thump each fist in turn while reciting the One Potato or Eenie Meenie lyrics. The person whose fist was thumped on the final word of the poem could withdraw their fist, and the poem would begin again until only one fist was left, and that person would be It.

As you might imagine, this process sometimes took as long as the game itself.

As mentioned above, Duck, Duck, Goose was also popular, and you didn’t need snow for that, just a circle of kids squatting down while It went around tapping them on the head saying, “Duck, duck, duck, goose.” Whoever was the Goose had to jump up, chase It around the circle and catch them before they got back to the spot the Goose had been in. If the Goose didn’t catch It, then they would be It and the game would continue.

This was clearly more exciting than playing Call of Duty on your Xbox.

Tag (and I cannot believe I am describing this game) was even simpler. Just have It chase the others around until they caught one of them, and then they would be It. (Have I mentioned yet that things were simpler back in the Colonial Era?) The game could, however, be spiced up a bit by adding new features, like Frozen Tag, or Squat Tag.

Hide and Seek was also popular, and involved (in addition to selecting It) a protracted period of deciding the Rules: How far to count, whether the “Anyone around my base is automatically It” rule should be enforced, whether It had to give fair warning that their count was coming to an end, etc. Just because we didn’t have WiFi doesn’t mean we weren’t civilized.

Jump Rope was another game that seemed to spontaneously appear, along with rhymes that no one had to teach us. The most common were counting rhymes, the purpose of which was to see how long you could jump without making a mistake:

My little sister dressed in pink

Did the dishes in the kitchen sink

How many dishes did she break?

1, 2, 3, 4, 5…

Or

Cinderella, dressed in yellow

Went upstairs to kiss her fellow

How many kisses did she get?

1, 2, 3, 4, 5…

(Seems there were a lot of rhymes about kissing)

Janey and Johnny (you would substitute the names of two people you wanted to embarrass)

Sitting in a tree,

K-I-S-S-I-N-G

First comes love,

Then comes Marriage

Then comes Janey with a baby carriage.

And the timeless…

Teddy Bear, Teddy Bear, turn around, (jumper turns around)

Teddy Bear, Teddy Bear, touch the ground, (jumper touches ground)

etc.

For Hopscotch, all you needed was a small stone, some chalk and a flat bit of concrete. There were numerous ways of drawing a Hopscotch board, but this was the one we favoured:

threatened with criminal damage for drawing a hopscotch board,

which shows this game is still (barely) alive, but won’t be for long.

The idea was, you threw the stone into the squares starting at one and going up to ten. If you got your stone in the correct square, you had to pick it up, but you did so by jumping on alternating feet, though the numbers, until you got to that square, then you had to pick the stone up, without touching the ground, while standing on one foot.

You took turns throwing your stones, and the first person to ten (or up to ten and back to one again, depending on how bored you were) was the winner.

If you were alone—as you often were when and where I grew up—you could play Russia. All you needed was a rubber ball.

The rules were simple. You’d throw the ball up and catch it. Then you’d throw it up, let it bounce, and catch it. With each throw, there was an added complication until you were doing things like throwing the ball up from under your leg, spinning around, clapping your hands, etc. Although a solo game, it could be played in a group, with the winner being the person who got to the highest number before missing the ball.

I am not sure where this game originated or how it came to us. It isn’t anything I can find in Google and appears to be a variation of Seven Up, but without the wall, so perhaps we took to it because, although we had rubber balls, we didn’t have any adequate walls to bounce them off.

There were, of course, other games, and the original purpose of this article was to chronicle the games we played up to and including our teenage years, but I am already over my word-count, so I think I’ll leave that for another time.

PS: In discussing this article with my wife, I see that it is heavily skewed in favour of a few games. There are many, many fine games (Red Rover, British Bulldog, Kick the Can to name just a few) I left out because—due to a lack of participants—we never played them. It was also interesting that, like my experience, she and her friends spontaneously started playing these games, without any instruction or intervention. And, despite being from different countries, many of the games, as well as the rhymes, are identical.